Finding Hope in Horror

The horrors persist and so do we.

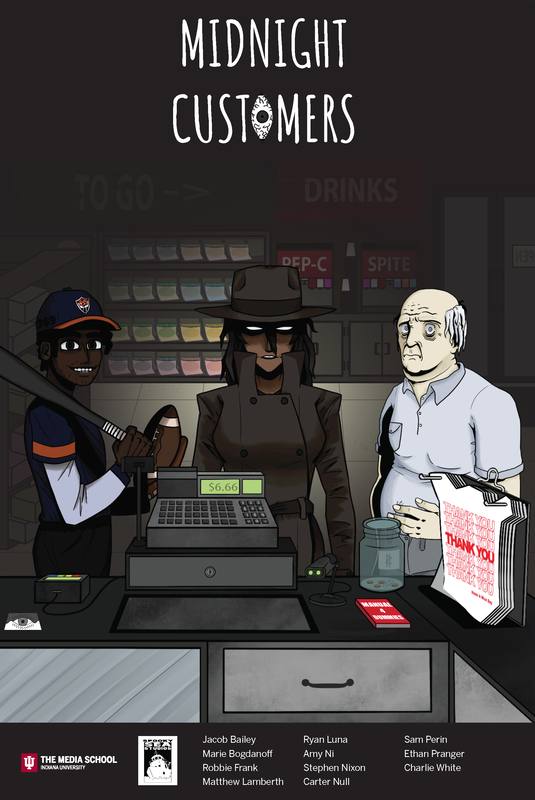

The first published game I ever worked on was for a capstone project in college. Our class had been divided into several groups, each with their own game and mine had just been dissolved. I got shuffled into one that was working on a narrative-driven horror game titled Midnight Customers. I was bummed about not being on my original project. Still, the premise for this one seemed alluring enough: a Lovecraftian horror where you play as a gas station clerk in the middle of nowhere on the graveyard shift meeting a whirlwind of the weirdest characters and creatures possible.

Now I’ll have to be honest, I didn’t have the faintest clue what I was doing. I had only started taking writing seriously the year prior and hadn’t the faintest clue how narrative design worked for video games. What better way to learn how to swim than to just jump in a pool that you can’t see the bottom of? So, I learned and fumbled my way through it all. I made a host of mistakes and created things I’m proud of. Even if I’ve improved, everything I wrote then was part of a journey to being better.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about that period of my life a lot, and one of the biggest things I missed when trying to write that horror game. As part of my full transparency, I’d like to admit that Midnight Customers didn’t end up being much of a horror game. It ended up being more of a thriller with a lot of one-off moments that consisted of everything from comedy to social commentary to both.

Prior to this point, I didn’t even like horror. I would think, “Being scared for fun? I’m just a boy! I just want to relax!” However, I tried to research and force myself to watch and play through as much horror as I possibly could. Through it all I found a genuine taste for it, which was weird. I always feel like the most anxious person alive, so why does horror draw me in? I think it was the most crucial thing I was missing while working on Midnight Customers: hope.

Hope is a craving many of us have in the real world, but it’s also a narrative vehicle. I sit here writing this with AMC’s The Walking Dead on in the background, and I’ve been asking myself, “Why keep going?” The show wrestles with this question a lot as well. The answer the show seems to find a lot is “for each other.” Most of the characters have someone to live for, someone to hope for.

This, of course, could be re-labeled as a character motivation, but I think that’s too broad for what I want to express. The hope that I’m talking about is a far deeper, intimate motivation. Take Dead Space, for example. Dead Space drops its protagonist, Isaac Clarke, into a desolate spaceship where almost all of its inhabitants have become horrid monsters named Necromorphs. I want to stop here and let you consider what you would do in this situation. Personally, I would turn the ship around and simply leave. What’s on that decrepit ship is none of my business! Isaac, however, has someone he loves on that ship, Nicole. He has a reason to be there, an investment. He shoots and stomps his way through that ship for her. For the sliver of hope that she could be alive and that he might be able to hold her in his arms again. This is the hope I’m talking about.

What makes horror so effective is the threat of taking something so close to someone away. When players step into the shoes of Isaac Clarke, they get his lens. His motivations. They see the first message from Nicole yearning to have a chance to talk to Isaac again, and hear a colleague mentioning Isaac had been playing the message repeatedly to himself. This is all to guide the player into wanting to step onto the derelict ship too. To find out both what’s happening, and what happened to Nicole. Of course, there’s immediate ambiance, music, and set pieces that lend themselves to the genre all created by masterful artists and designers. Still, the long-term driving force is that hope.

Oddly enough, one of the first horror games I played all the way through was the Resident Evil 2 Remake. I was a freshman in college and had just been put on academic probation. I was far from home, depressed, lost, and barely spoke to my roommate. I wasn’t working at the time either, so blowing money on a new $60 video game was probably not the greatest decision, but who doesn’t make poor financial decisions at the behest of mental illness?

My roommate walked into our dorm the night I bought it, and his face lit up. “Oh shit, dude. I’ve heard that one’s really good,” he said. I asked if he wanted to watch me play it and, from there, we bonded. The driving force for that game is far simpler than Isaac Clarke’s situation. Two strangers, Leon and Claire, meet during a zombie outbreak and spend the game trying to find each other again while also uncovering how the outbreak began. Simple, but enough. We immediately decided that Claire had to be protected at all costs and that Leon had no business being a cop so perhaps his predicament was for the best. I would pass the controller to him when I got too scared but ripped it out of his hands to fight the final boss. I’ll be damned if anyone lays a finger on the poor little girl Claire had found.

It's a game that probably kept me from dropping out, and made me a lifelong friend in the form of my roommate. If Leon and Claire could make it through what seemed like the end of the world and still have each other, then I felt like maybe I could make it through what I thought was one of the lowest points of my life.

When I began work on Midnight Customers, my father died. I stayed home for a semester and did everything from home. That’s when I began all of my horror research. I think I was desperately chasing that same feeling. Watching characters go through hell and back for the people they love, the dreams they have, and the aspirations they hold. Was anything I experienced akin to that of alien monsters ripping people apart? No…probably not and I’m fairly okay with that, but I think the genre serves a purpose in reminding us of why we keep going.

Hope.

Edited by Marie Bogdanoff