The Militarization of Mass Effect

What if humanity did imperialism in space and we were all cool with it?

I was eight years old when I saw my first war film, Saving Private Ryan. A World War Two movie in which the beginning is lauded as having the most gruesome and realistic depiction of a D-Day beach landing in cinematic history. The appropriate reaction to this fact is, “Who allowed this?” The quick answer is my father was the one always putting these movies on. He was a big World War Two in Color guy, and my little spongey child brain latched onto this passion very fast.

From then on, I watched anything with guns, swords and tacti-cool army guys doing what I assumed was “protecting my freedom.” It also seemed like so many bits of media were feeding this growing obsession of mine. I started playing Halo and Call of Duty at the age of ten, and airsoft by the age of fourteen. I even had the intention of volunteering for the Marines when I turned eighteen.

As I grew into adulthood, I learned more about the context and history of US military intervention, and thus my taste for these things died down significantly. I even tried watching Black Hawk Down the other day and couldn’t finish it despite my desire to see Ewan McGregor do anything. Despite this, there is a particular game series that has kept itself lodged in the part of my brain I call the “feral obsession corner.”

Now, Mass Effect has so much going for it that makes me smile so wide and sweat so much. Between the cool action set-pieces and the wonderfully intimate character moments, there’s a lot to love! Yet, each time I play through the series, I notice something: Mass Effect loves the military.

It’s easy to say something like, “It was 2008! It was a product of its time!” Sure, much of the US populace was particularly bloodthirsty and gung-ho about supporting the troops after 9/11 and funding for military propaganda skyrocketed with Go Army ads and video games. I specifically remember American flags being quickly sold out at every store.

However, many condemned the invasions and there were veterans who loathed their time in the military. There were even celebrities who spoke out against the invasion of Iraq, such as Michael Moore at the 75th Academy Awards. So, why make a whole sci-fi series that devolves into how awesome and cool humans are at war? That’s a question I’ve been asking myself for years in the most disappointed tone possible.

The first Mass Effect takes place in the Milky Way Galaxy several decades after humans have discovered advanced space flight and aliens. The player takes control of Shepard, a Commander in the Human Alliance military. They are tasked by the intergalactic government, the Council, with tracking down a rogue agent named Saren who is hellbent on summoning a deadly mythical race of space robots, the Reapers. We see visions of destruction and get told we are crazy in almost all instances it gets brought up until the very end when *gasp* the Reapers are real!

Between the moments of chasing down Saren, there are some very deep and well-written companions like Wrex, a disgruntled warrior whose people have experienced centuries of genocide at the hands of the Council. There’s Kaidan, the resident awkward man with a heart of gold and a life of trauma at the hands of the military. There’s some wonderful room for critiques and connections to real history. Then there’s Ashley, the space racist. I could write pages on how odd it is to have a character that is akin to that one uncle with “theories” on immigration, but I want to focus more on how she is a career military woman and the biggest alien hater because of her experiences with it.

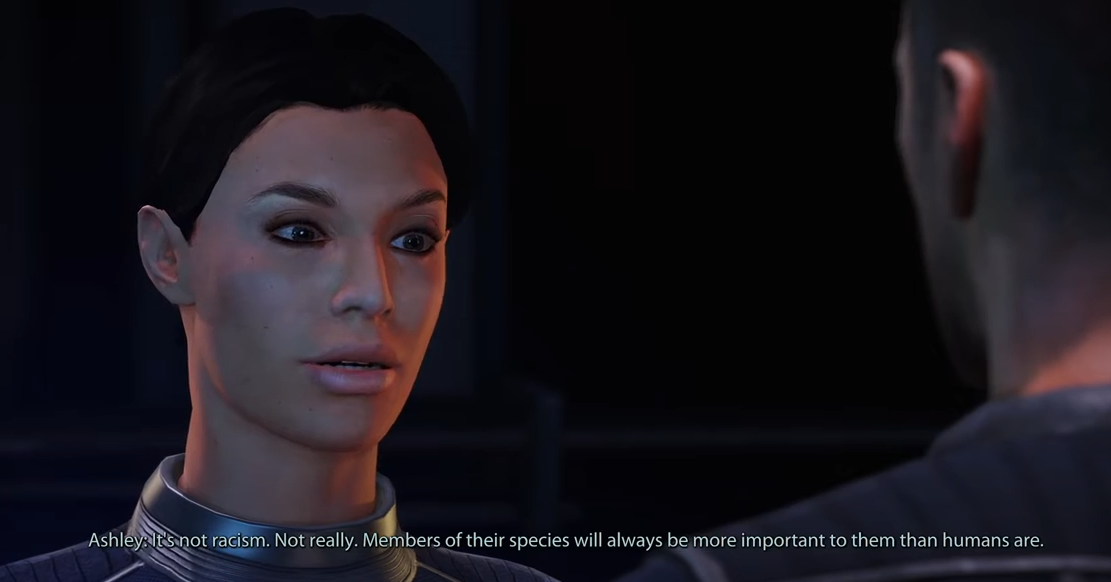

On one hand, you could say this is a good addition to showcase the one-sidedness of post-9/11 attitudes. The deep racism and the effective propaganda from the government saying, “This isn’t our fault! We never do anything wrong!” However, the game doesn’t necessarily discourage her attitude. Instead, she maintains them throughout the games so long as you choose to save her over Kaidan as a major player decision. The game gives the player some opportunities to disagree with her to which she replies with sentences like, “It’s not racism, not really,” without any further pushback allowed.

Ashley’s father was part of the First Contact War, a conflict between humans and the other Council races after humanity first made contact with them. Since then, Ashley has borrowed her father’s distaste for the other races and enlisted with the goal of protecting human freedom. A big bold line could be drawn connecting this with those who enlisted after witnessing the events of 9/11. My mother worked with a man a few years ago who had enlisted the day of the attacks and relished in making Islamophobic and xenophobic comments.

As an antithesis to Ashley’s patriotic humanity, Kaidan highlights his worst experiences in a military academy, in which he was abused and tormented until he accidentally killed his abuser, the instructor. It’s a painful memory he relives with Shepard, and it makes for such a profound moment of vulnerability.

Kaidan’s experiences at the beginning of his military career were a result of Alliance-sanctioned and corporate-backed experiments and training. He was separated from his family as a teenager. He was starved. He was brutalized. After, he mentions that he only enlisted for the paycheck and to make his father proud.

That sounds like a great commentary on why many enlisted right? Pressure, paycheck, etc.

By the third game, Kaidan is a Council agent, a Spectre, and elated to be one. He’s also been promoted within the Alliance a few times in between games. He’s fully bought into his service and even has a conversation with Shepard about how amped he is to have been asked to become a Spectre. Despite all the player had learned about him, he never acknowledged the root of why all of this happened to him: the Alliance’s desperate rush to become a military superpower.

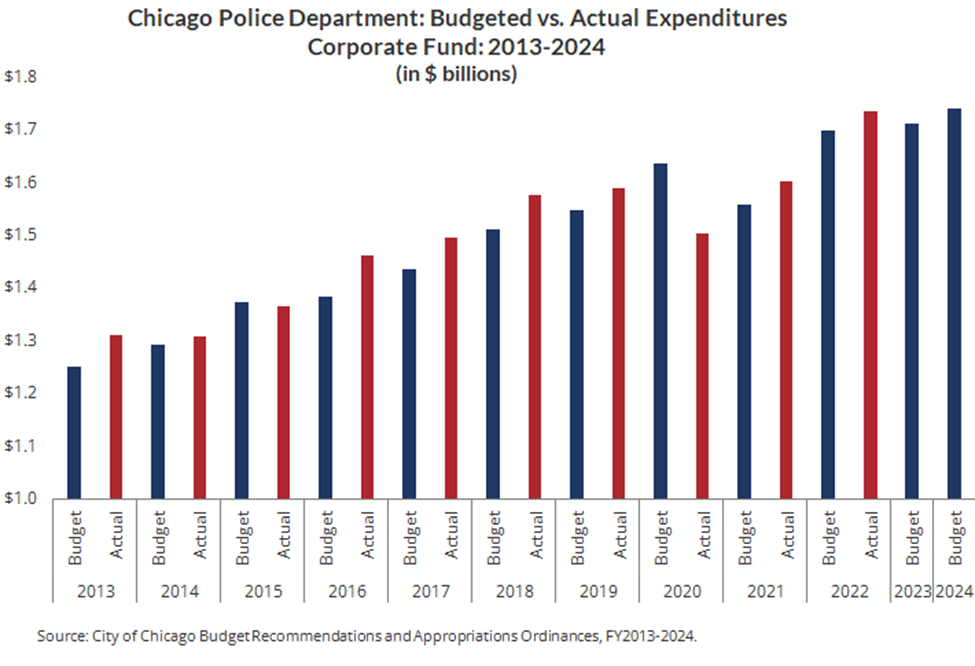

There’s also something to be said that Garrus, the cop turned space vigilante, is brought onto the ship and immediately complains that he can’t shoot people more. That is to say that there is surely not a lot of distinction between a cop and the military in post-9/11 USA. Throughout the last twenty-three years, police budgets have gone up astronomically along with their equipment becoming far more militarized with armored vehicles, riot gear, and assault weapons.

One of the first encounters with Garrus involves him endangering a hostage by shooting at the man holding her. No visible consequences are seen for his erratic and violent behavior. Instead, he’s brought right on board. On the bright side, the player has many opportunities to tell him that murder is wrong. So, that’s something!

In Mass Effect 2, there’s an opportunity that arises. Shepard has cheated death and is no longer in the Human Alliance. They’re forced to work for a human supremacist organization, Cerberus, as a quasi-prisoner. This game has no issue showing us the horrors of this organization: the unethical experiments, the betrayals, the hefty racism. When the game ends, the player can choose to break free from them and defeat a Reaper. From there we are left to wonder what we will do next. The Alliance has effectively denounced Shepard for becoming a Cerberus lackey. So, what now?

In my mind, we are preparing for a Reaper invasion, and we have seen the petty squabbling and horrendous actions of organized militaries. Why not go independent? Shepard has been seeking their place in both the galaxy and history, so why not forge their own path? I expected Shepard to start alone with their ship, their crew, and their wits and slowly build the allies around them. Squashing beef and uniting the races with no ulterior motives.

A silly little train of thought.

Within five minutes of Mass Effect 3, we are already back with the Alliance and on house arrest. It turns out that Shepard has turned themselves in! The Council has become space NATO by this point, with humanity having a seat on it, and tasks Shepard with uniting all other governments and militaries left in the galaxy during the Reaper invasion. Shepard does all of this after being disrespected and gaslit by both the Council and Alliance politicians for two whole games. Perhaps I, as Shepard, can yell at them! I could be a bit of a rogue who uses the desperation of the Alliance for a Reaper expert to my advantage. They can’t fire me, but no. No, instead Shepard loves them. Shepard accepts orders yet again and is dead set on proving humanity’s place in the galaxy with the barrel of their gun and the ability to yell only at other aliens. They’re the silly ones. They never believed Shepard. Don’t think too hard about how the Alliance also just didn’t believe Shepard for the majority of Mass Effect 2. You’d just get a migraine.

Mass Effect is a franchise that I love so deeply but I would be remiss if I didn’t think about its flaws. It’s because I care about it that I want the series to be better. I love how Garrus evolves into this bro of a character, giving advice and support to Shepard through the stressors of intergalactic extinction. I love how Liara, another companion, becomes this underground criminal mastermind as well as a shoulder to lean on between Shepard’s recurring nightmares in Mass Effect 3 (she also dedicates a time capsule to you! I melt!). I have hopes for Mass Effect 4, and with the exhaustion many have with our government’s obsession with being the “world police” to the detriment of everyone around it. Maybe the tune will change because I am so tired, reader. I am tired of seeing what are essentially Go Army advertisements seeping into the cracks of stories I want to love so badly. I believe we can and will do better, it just may take a few conversations with ourselves about what the US uniform and the flag can mean to anyone else outside of our borders. From there, some deeply impactful stories about the realities of war and militaristic intervention can arise.

Edited by Marie Bogdanoff